|

Flash Flooding

>> The number one direct weather-related

killer in the United States

|

|

|

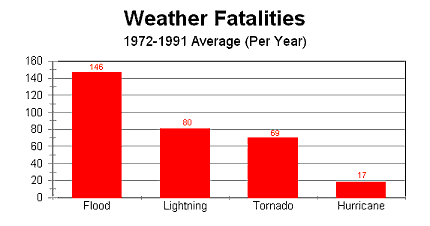

Figure 1:

The graph above shows that floods have caused the most weather-related

deaths in the United States from 1972-1991. |

Flash flooding is the number one

weather-related killer in the United States. These floods, which generally

occur within six hours of the onset of precipitation, killed over 10,000 people

in the United States since 1900. Figure 1, found to the right,

compares the deaths due to flooding with other fatal weather events.

>> Occurs when more rain falls than the ground can absorb and when it falls

heavily enough to cause sudden, rapid runoff

>> Atmospheric factors

There are three primary ways flash flooding episodes develop. One important factor

is the strength of the upper-level winds. Very weak upper-level steering

winds can work to cause slow-moving and/or stationary thunderstorms. This

will cause the thunderstorms to dump a large amount of rain over one specific

area for an extended period of time.

Flash flooding can also be caused by

multiple thunderstorms continuously forming and moving over the same spot.

This atmospheric process is called training.

Finally, flash flooding can be caused by

orographic lifting, when a moist and unstable airmass ascends the side of a mountain and the prevailing

winds continue to blow additional moist, unstable air to the same location.

Microbursts

>> Exceptionally strong thunderstorm

downdraft caused by unusually strong evaporational cooling

|

|

|

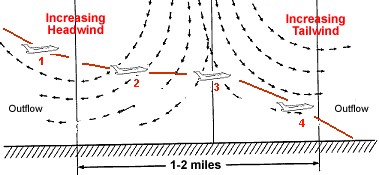

Figure 2:

The image above shows the difficulty airplanes face when encountering a

microburst while landing. |

A microburst is an exceptionally

strong thunderstorm downdraft that is caused by unusually strong evaporational

cooling within the storm. These microbursts can cause strong straight-line

winds that are often in excess of 100 miles per hour. They are also a

major threat to landing aircraft as they cause a large difference in wind

direction over a very small distance. The impact of microbursts on

airplanes can be seen in Figure 2 to the left.

Hail

>> Pieces of ice formed in the

thunderstorm's updraft

>> Also known as the "white plague"

>> Ingredients needed for hail formation

|

|

|

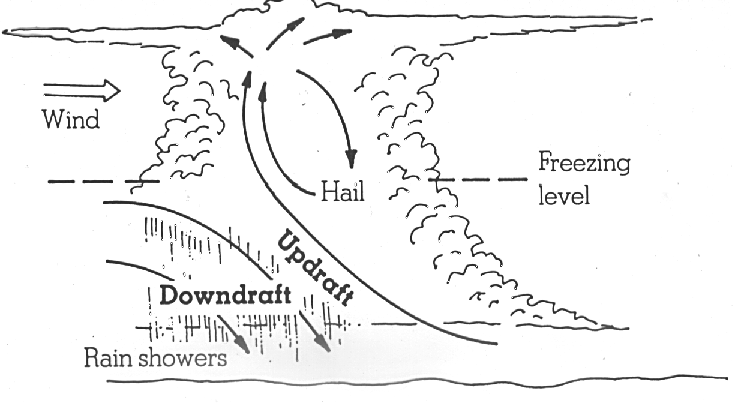

Figure 3:

The image above illustrates the process of hail formation in a thunderstorm.

|

A few key ingredients are needed to

produce hail. The first: freezing air needs to be

located relatively close to the ground, but not TOO close.

The second and most important

ingredient for large hail formation is a strong updraft. The updraft needs

to be strong enough to support the ever-growing hailstones. Once the

updraft can't support the hailstones any longer, they fall out of the

thunderstorm toward the ground. The process of hail formation can be seen

in Figure 3 to the right.

Organized Thunderstorm Complexes

>> Squall Line: A band of

thunderstorms that often forms well ahead of a cold front

A squall line is a band of

thunderstorms that often forms well ahead of a cold front. In order to

produce a squall line a rich supply of warm, moist air is needed. This

requirement is often met if there is a low-level jet stream present in the area.

This low-level jet will work to bring warm, moist air in from the south.

In addition to the presence of warm,

moist air, these squall lines often form in association with large upper-level

divergence and large scale lifting. This is why squall lines are most

often found ahead of a frontal system. A squall line can be seen moving

through Pennsylvania in the radar loop below.

|

|

|

Figure 4:

The radar loop above shows a squall line moving through Ohio and

Pennsylvania on August 24, 1998. |

>> Mesoscale Convective Complex (MCC):

Primarily nocturnal bundle of thunderstorms that stretch across hundreds of

miles

|

|

|

Figure 5:

The satellite image above shows a mesoscale convective complex over

Oklahoma. |

The mesoscale convective complex is a

nocturnal bundle of thunderstorms that stretch across hundreds of miles.

Much like a squall line, the low-level jet stream feeds warm, moist air into

these thunderstorm complexes. In this case, however, a mid-level low

pressure forms within the group of storms. This low pressure helps to

sustain this large group of thunderstorms. Mesoscale convective complexes

are very common in the Plains states and help to provide a good majority of the

rain throughout that area. An infrared satellite image of a MCC can be

seen to the left.

|